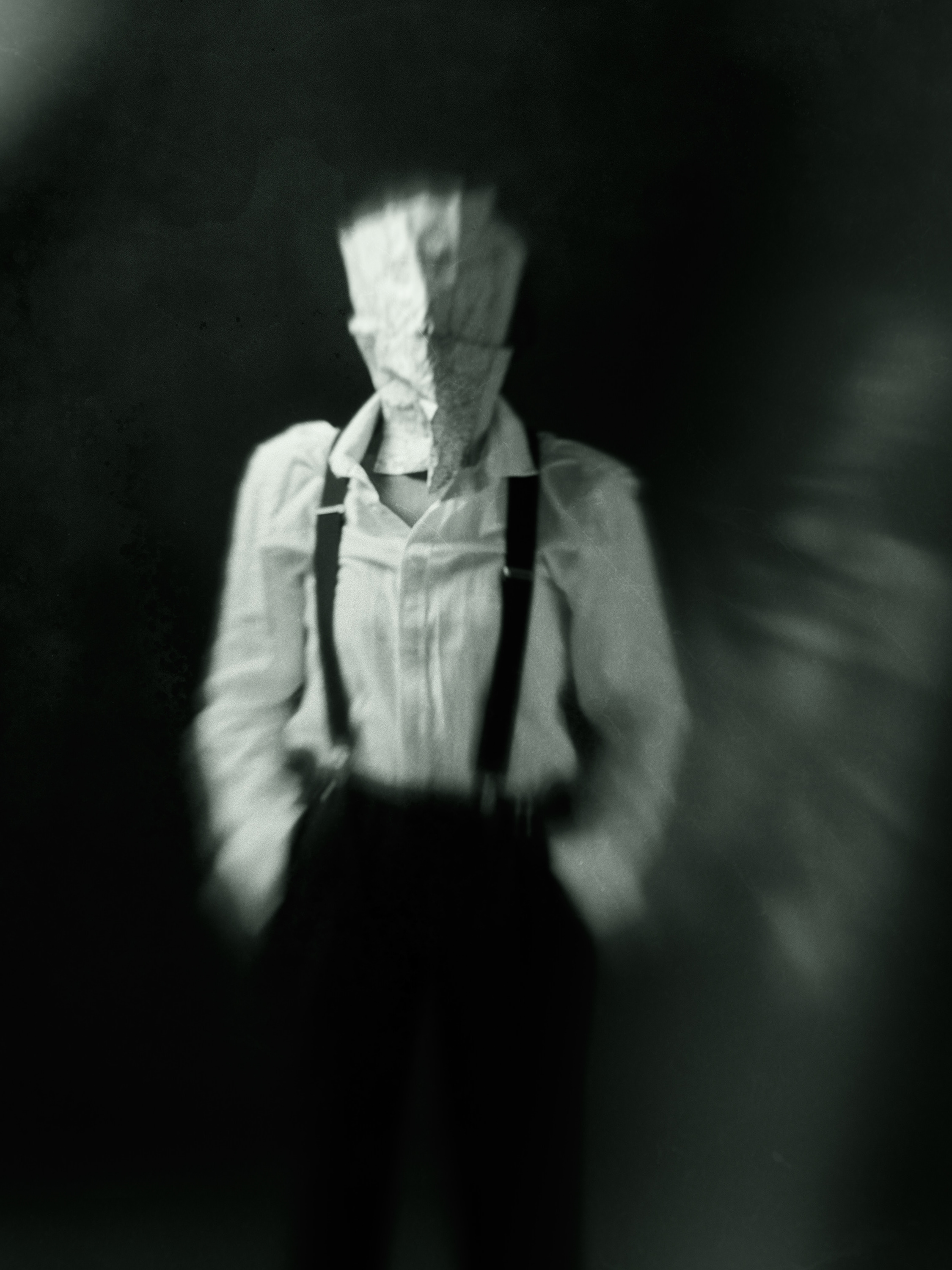

You’re probably familiar with Magritte’s famous, playful paradox: Ceci n’est pas une pipe – This is not a pipe. In his painting, he reminds us that what we see isn’t a pipe, but a representation of one. The painted pipe cannot be filled, lit, or smoked. It performs none of the functions of a pipe. It only gestures towards the idea of one. A modest but profound provocation: the image is not the thing.

Magritte was speaking about painting, a medium of invention. But what of photography? Is it merely another form of representation – or something closer to the real?

Unlike a painting, a photograph is not conjured from imagination. Light from a real object impresses itself onto film or sensor. The image is not a symbolic construction but a trace, a residue of presence, a physical testimony that something once was. This direct, causal link grants the photograph a particular authority, a claim to truth. The photograph does not simply depict the world; it records it.

So, in theory, what you see in a photograph is a pipe. Its image is anchored in reality, secured by light. You can almost feel the weight of its existence, as though the object still lingers behind the glass of the image.

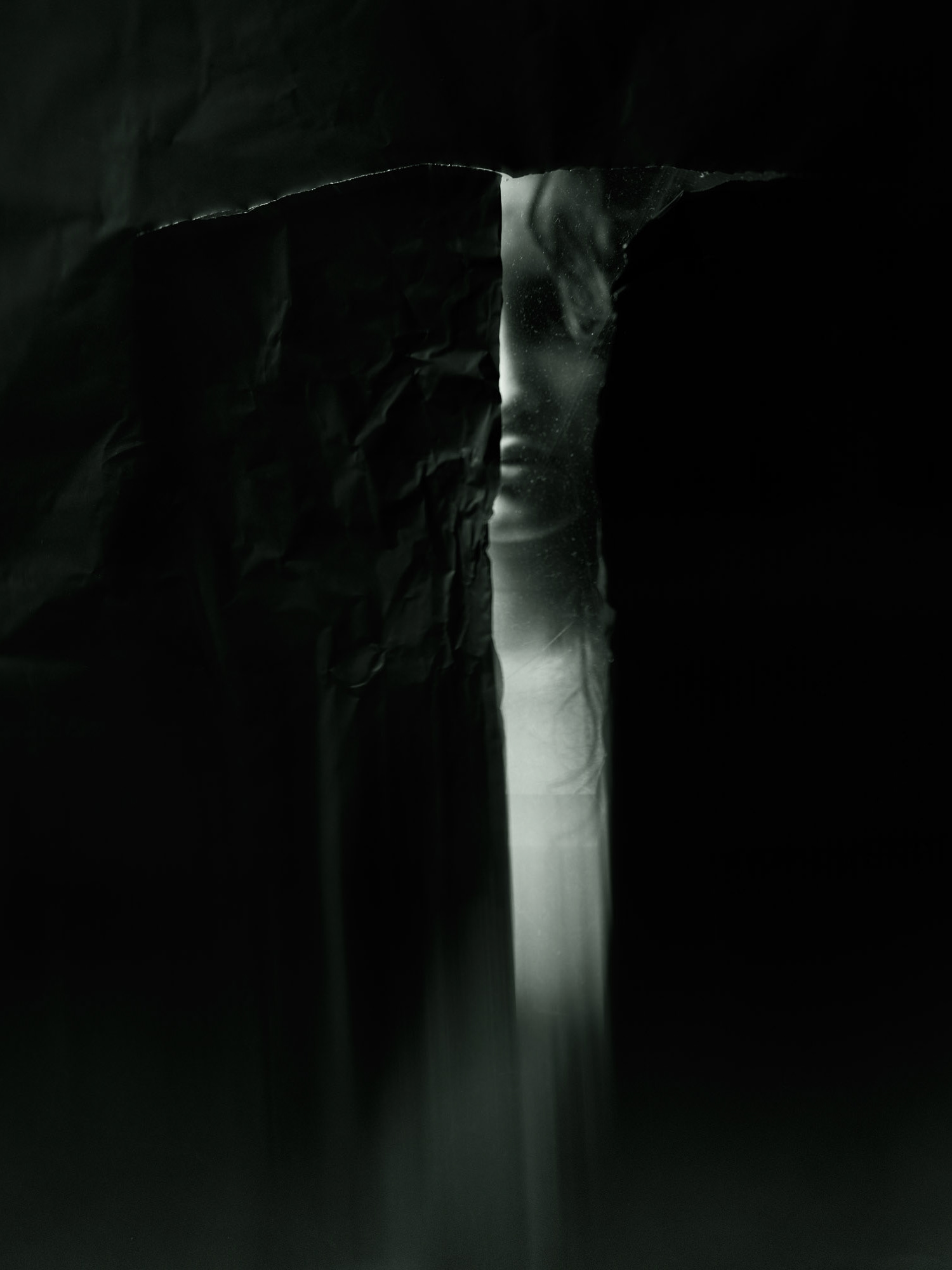

Yet this certainty is deceptive. Framing, perspective, and omission shape what is seen and what is excluded. Every photograph is both evidence and interpretation, a fragment of the real filtered through intention, chance, and time. It tells the truth of a moment that no longer exists.

Perhaps this is the photograph’s quiet paradox: it stands as proof and illusion at once. It assures us that something was there, yet that very assurance distances us from it. The photograph transforms the living into the still, presence into memory, existence into representation.

So, yes, in theory, what you see is a pipe. But it is also a ghost of a pipe, an image that insists on reality while simultaneously erasing it.

Still, I’d take this pipe with a pinch of tobacco.