There are many ways to learn how to see, and just as many ways to learn how not to. I’ve often wondered how much of our adult vision — the way we look at people, places, and ourselves — is shaped not by what we were shown as children, but by what we were quietly asked to ignore.

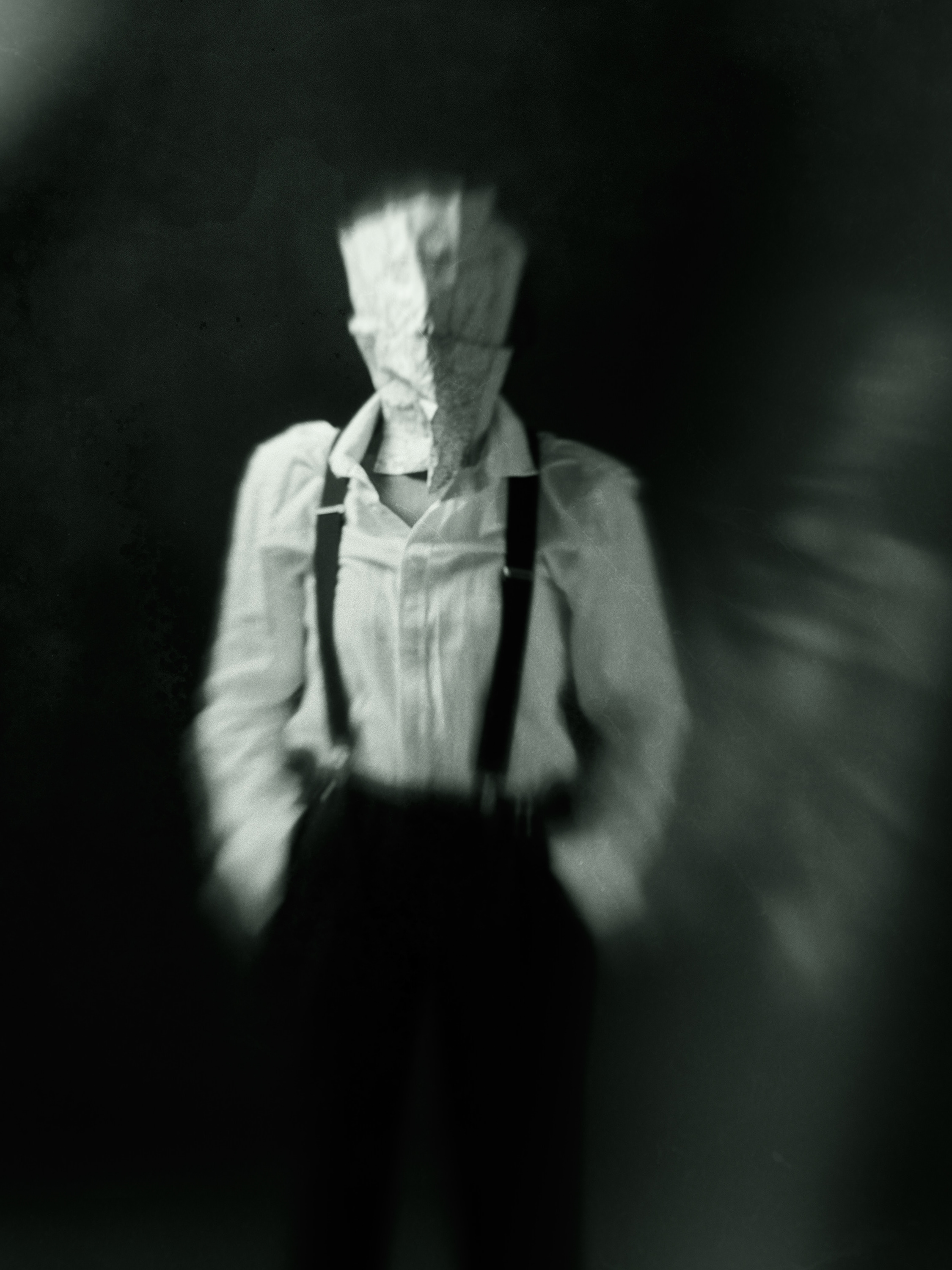

My childhood home had a peculiar dynamic. Probably not unique, yet distinctive enough to mould the way I perceive the world. Early on, it became a small, human-made universe where not seeing became as essential as seeing. I grew up in a house where things were swept under the carpet, where silence was the language of survival. Remarks lingered in the air instead of unfolding into open conversation. Heads turned away. Eyes deliberately closed. I learnt not to see, even when I was looking.

Looking back, I realise our home was full of elephants in the room. My father lived a grand and unapologetic life, with little regard for his marital vows. My mother, in turn, chose not to notice. On the surface, we were a loving family. The illusion of normality was carefully maintained. My mother worked hard to protect it, refusing to hear the roar of the elephant in the room.

Acknowledgement would have led to confrontation, confrontation to change, and change to the collapse of our fragile equilibrium. So, for the sake of peace — and perhaps dignity — our family story was gently edited, curated to show only its idyllic side. Everyone around us knew better, of course, but they too chose to play along, as if our shared silence were some kind of polite agreement.

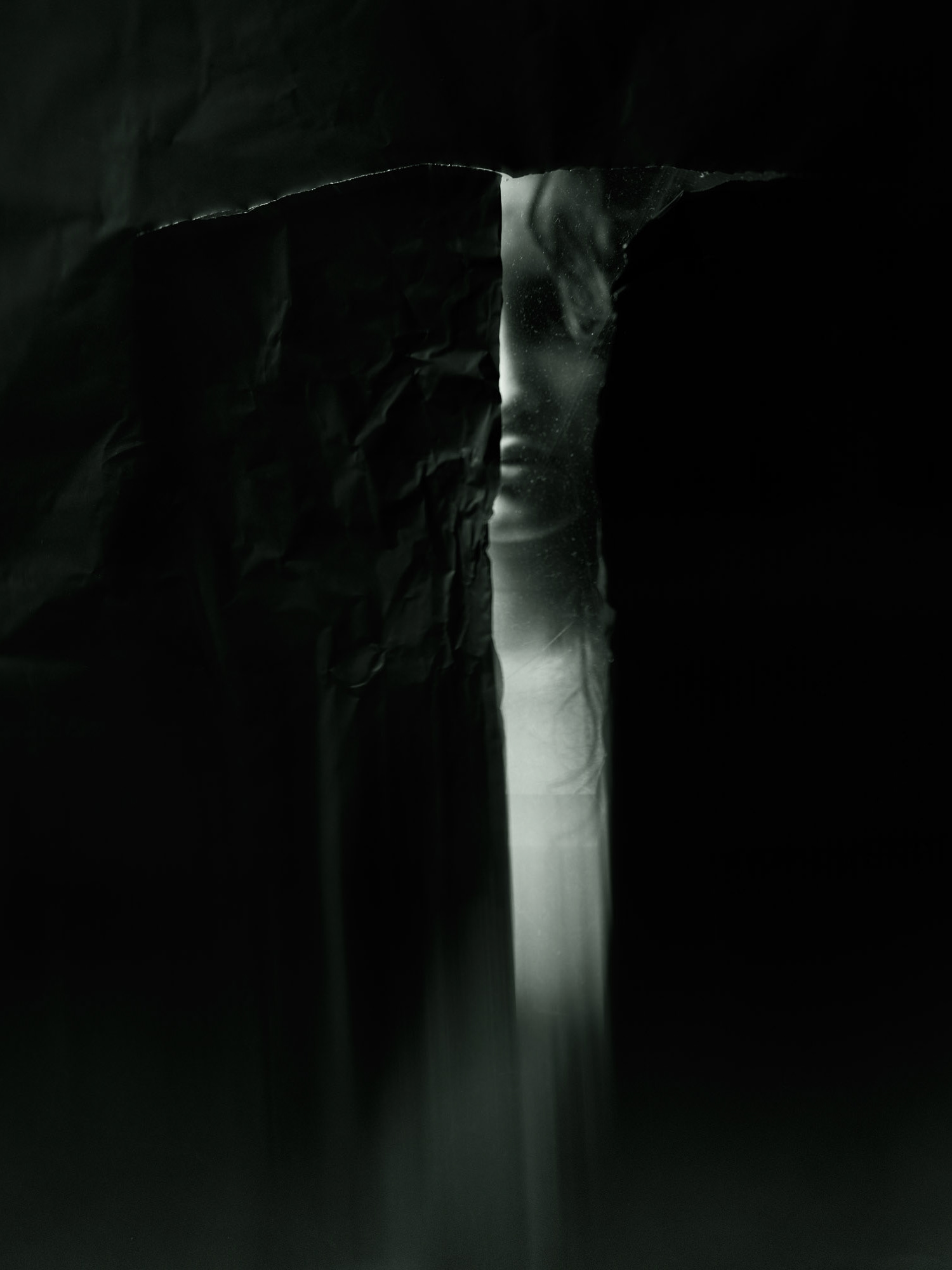

Not seeing things became my first life lesson. I learnt how to squint until the picture lost its sharp edges, softening the details that might otherwise pierce my thoughts. I learnt how to look away quickly, avoiding the things that demanded reaction. Seeing would lead to noticing, noticing to speaking, speaking to challenge — and that was forbidden. I became an accomplice in the quiet conspiracy to keep the family whole.

The only redeeming part of this was that I began to appreciate the beauty of the blurred. When details vanished, I could enjoy the world as a wash of soft tones and gentle outlines — almost impressionistic, uncluttered, and oddly serene. I grew fond of this kind of seeing, and, in time, I began to seek it deliberately.

My camera became a tool for revisiting that way of looking. The photographs I take often carry that same soft focus, that same dreamlike blur that defined my childhood vision. Sometimes I think photography is my therapy — a way of speaking about the things we never dared to name. It allows me to explore the quiet spaces between seeing and not seeing, between truth and illusion, between memory and imagination.

Perhaps, after all, there’s an art in not seeing things — not the art of denial, but of transforming silence into expression. In the blurred edges of my images, I find the outlines of the past softening, finally becoming something I can bear to look at.