When my grandfather was forty, there came a knock at his door. German soldiers stood on the threshold and told him, quite simply, that he no longer lived there. He had two hours to gather his belongings and leave, taking with him his wife and three children.

At more or less the same time, on the opposite side of the country, my great-grandfather watched his jewellery shop being looted and destroyed by Russian soldiers. He too was forced to abandon everything he had built. Both families had the ground pulled from beneath their feet by the same invisible force that reshaped the face of Europe.

My own experience was, of course, nothing like as harrowing or dramatic. Yet, decades later, when Europe opened up and the borders of possibility widened, I too decided to begin anew in a foreign land. I was almost forty when I packed my life into a few bags and left with my family, not knowing what awaited us on the other side.

Imagine finding yourself in a place where all you have are your skills, no family network, no old friends, no one to call in need. Just a suitcase and a toolbox in your head. It felt exposed, almost naked, but I was determined to make it work. And, in time, it did. After a few years, I can say with a smile that we all graduated from the university of life. What remains from those years is a quiet confidence: the knowledge that we are stronger than we think, and that even the mountains that seem unscalable at first can, with time, be climbed.

It wasn’t all struggle, though. There were moments of laughter too, like my first job interview in London. After just a few weeks in the city, I received a call inviting me to meet the editor of a magazine called Culture. The man’s deep, velvety voice conjured images of high-minded debate and literary prestige. I knew of Kultura, the legendary Polish émigré magazine published in Paris, and imagined its London counterpart to be a kindred spirit.

I didn’t own a proper suit, but I did my best to look the part. I got the job. Only later did I realise that Culture (in fact, spelled Cooltura) was a publication more “cool” than cultural, though the “cool” bit might have been a stretch. It was essentially a classifieds magazine with a section on events for the Polish community in London. Why it rhymed with Culture still baffles me. But it was part of the learning curve, and I treasure it for what it was: a first step.

There were countless other moments, some comic, others quietly difficult. But if I were to distil the migrant experience into two words, they would be isolation and determination.

I learnt new rules, joined a new game, met new people, and made new friends. Yet beneath the surface, there was always a quiet solitude, the ache of detachment that lingered even in the liveliest of gatherings. Meaningful conversations did happen, of course, but most of the time we skimmed across the surface, polite and friendly, yet never fully seen. Purpose and hard work made that solitude bearable. They gave it shape.

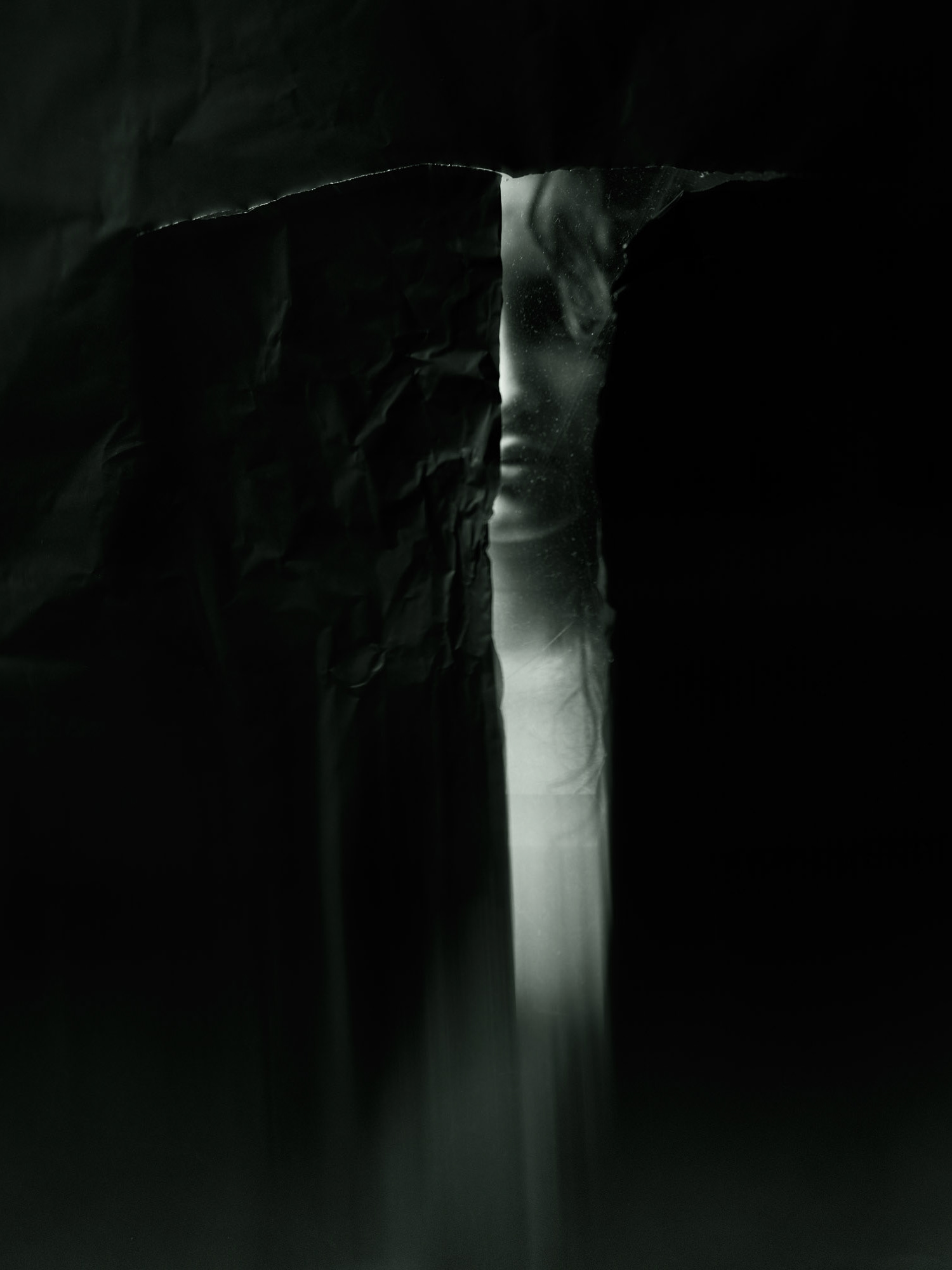

Out of that experience came Breakfasts at Maribel, a short story inspired by those early years, refracted through memory and metaphor rather than strict reality. It opens my collection Portraits for No One, which I have paired with a series of photographs and turned into a short film.

The first minute of it, The Arrival, is now complete, a small window into the journey that began all those years ago, with a knock on a door and the promise of a new beginning.

If you’d like to read Breakfasts at Maribel and other stories, please subscribe to my newsletter.

My stories are rooted in real life: in my own experiences and in moments others have shared with me, often in confidence. Some are sensitive, even intimate, and while I can’t retell them word for word, I’ve found that the lens of magical realism allows their essence to unfold gently.

Each month, I’ll send you a small booklet containing a story and a series of photographs that echo — though don’t necessarily illustrate — the narrative. These unpublished fragments from Portraits for No One are shared only with subscribers.