Every childhood home, I think, carries its own peculiarities. Small rituals that take root in the habits of parents and later bloom—sometimes wildly—through the lives of children. Nicknames, sayings, the particular way tea is made, or how the washing-up gets done. Each home is its own little universe, with gravity and motion and the occasional storm, all governed by familiar laws but tinged with a distinctive flavour.

My childhood home was no exception. We had our private vocabulary, our own set of household procedures, our small domestic myths. But there was also something less visible running beneath it all—a quiet undercurrent of mistrust. My father lived flamboyantly, often seizing any opportunity for pleasure, seemingly with little regard for his marriage vows. None of it stayed secret for long. I’m not sure how often my mother confronted him; I believe she did, but in the end, she chose to preserve the fragile structure of our family rather than dismantle it.

So, we lived in a kind of uneasy equilibrium. My father continued his life of distraction, while my mother maintained hers of quiet endurance. Their conversations were, on the surface, perfectly ordinary—about groceries, the weather, weekend plans—but always carried a subtext, a pulse of unspoken resentment. I grew up attuned to that duality: what was said and what was really meant.

Years later, when I discovered magical realism, I recognised something deeply familiar. Those layered realities, where the fantastical coexists with the ordinary, mirrored my own experience of childhood. The language of metaphor felt natural to me—it was the language of my upbringing. I had learned early on that truth often hides beneath appearances, and that meaning is rarely delivered directly.

We are shaped, I believe, by what surrounds us. Especially as children, when we absorb the world not by questioning but by osmosis. The duality of speech I grew up with became part of how I understood the world, and how I later chose to express it.

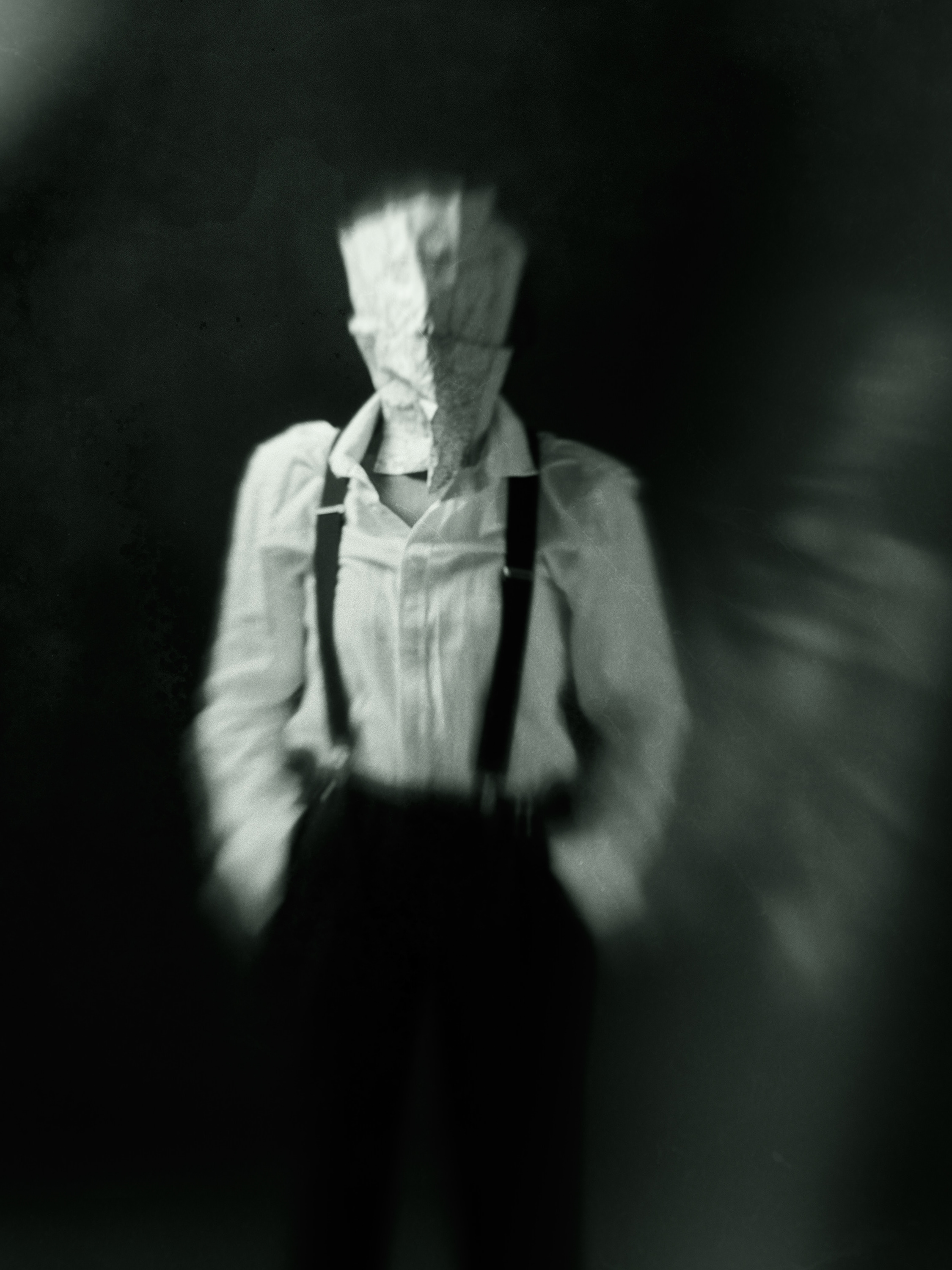

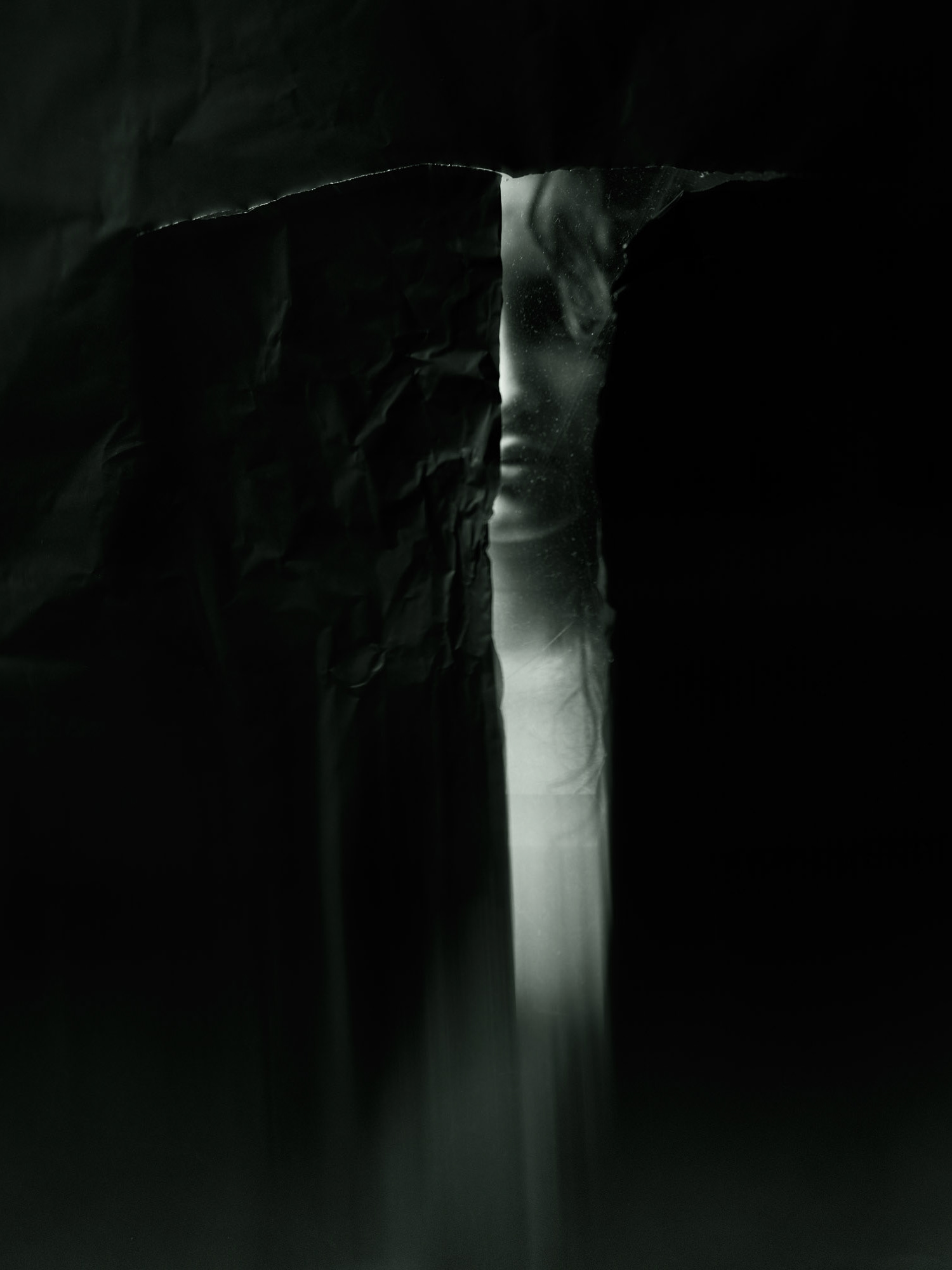

When I began photographing for what eventually became Portraits for No One—though it began under a different title—I found myself drawn into long, searching conversations with the artists and collaborators I worked with. They entrusted me with their most intimate stories: delicate, sometimes painful confessions that felt too personal to retell plainly. Yet they stayed with me, quietly demanding to be transformed.

So I began to write. A layer of words laid gently over the images, stories told through the lens of magical realism. It felt like the most honest way to speak of sensitive things—preserving truth, but cloaking it in metaphor. Portraits for No One became a crossover between visual art and literature, a dialogue between image and story, reality and dream.

Through that blending, I found a kind of reconciliation. The language of metaphor, the familiar ambiguity of magical realism—it all brought me home, in a sense. To the place where meanings are many, and truth, though disguised, still shines through.