People often ask why my images are so blurry. The answer isn’t a simple one — it’s layered, emotional, and deeply personal.

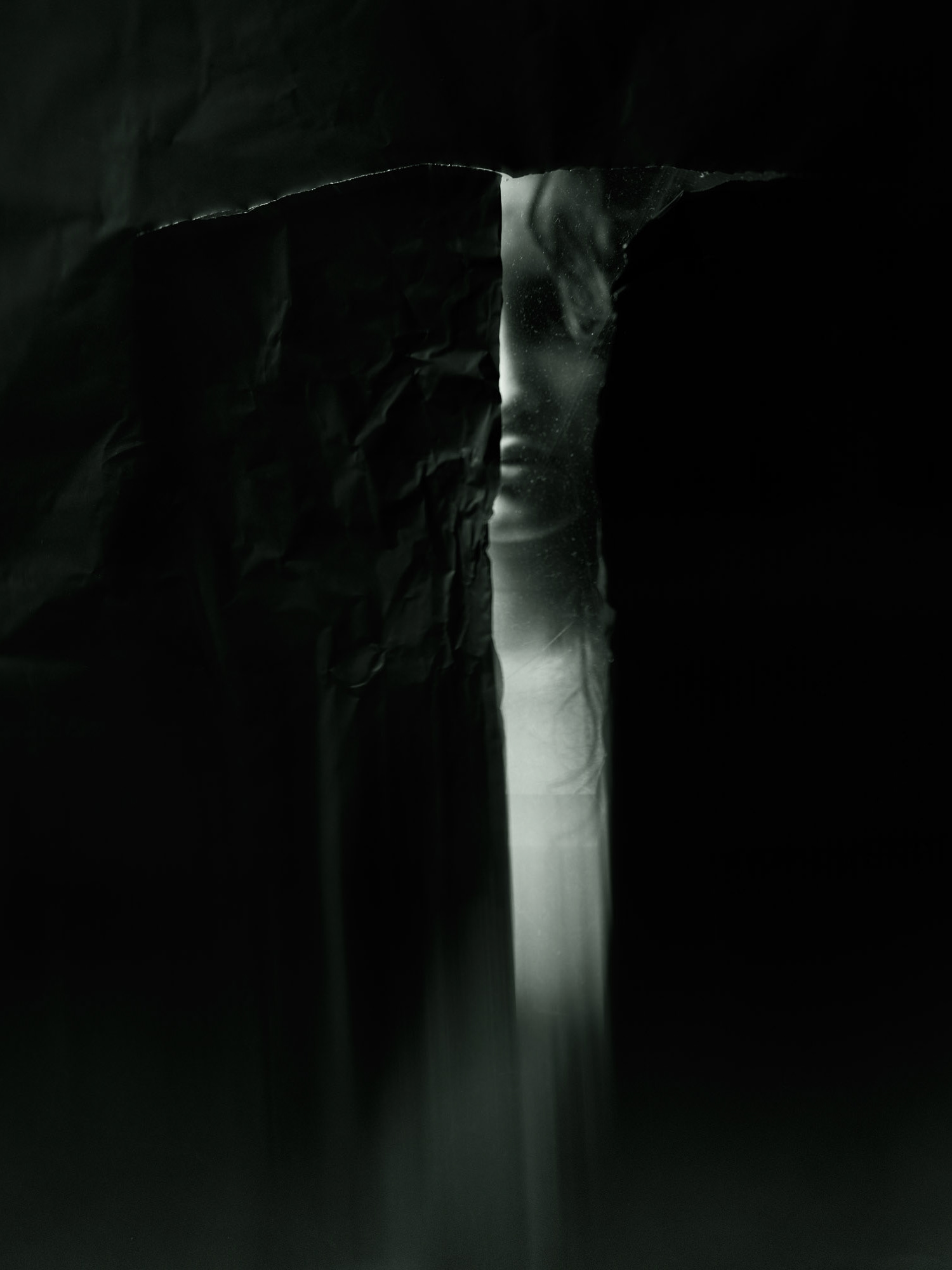

For me, each photograph is like a page torn from a private journal — a fleeting record of thoughts and feelings rather than a clear depiction of what stood before me. I’m not trying to show what I see; I’m trying to capture how I remember. And memory, by nature, is never sharp. It drifts, shifts, and softens — coloured by emotions, impressions, and the quiet echoes of the moment itself.

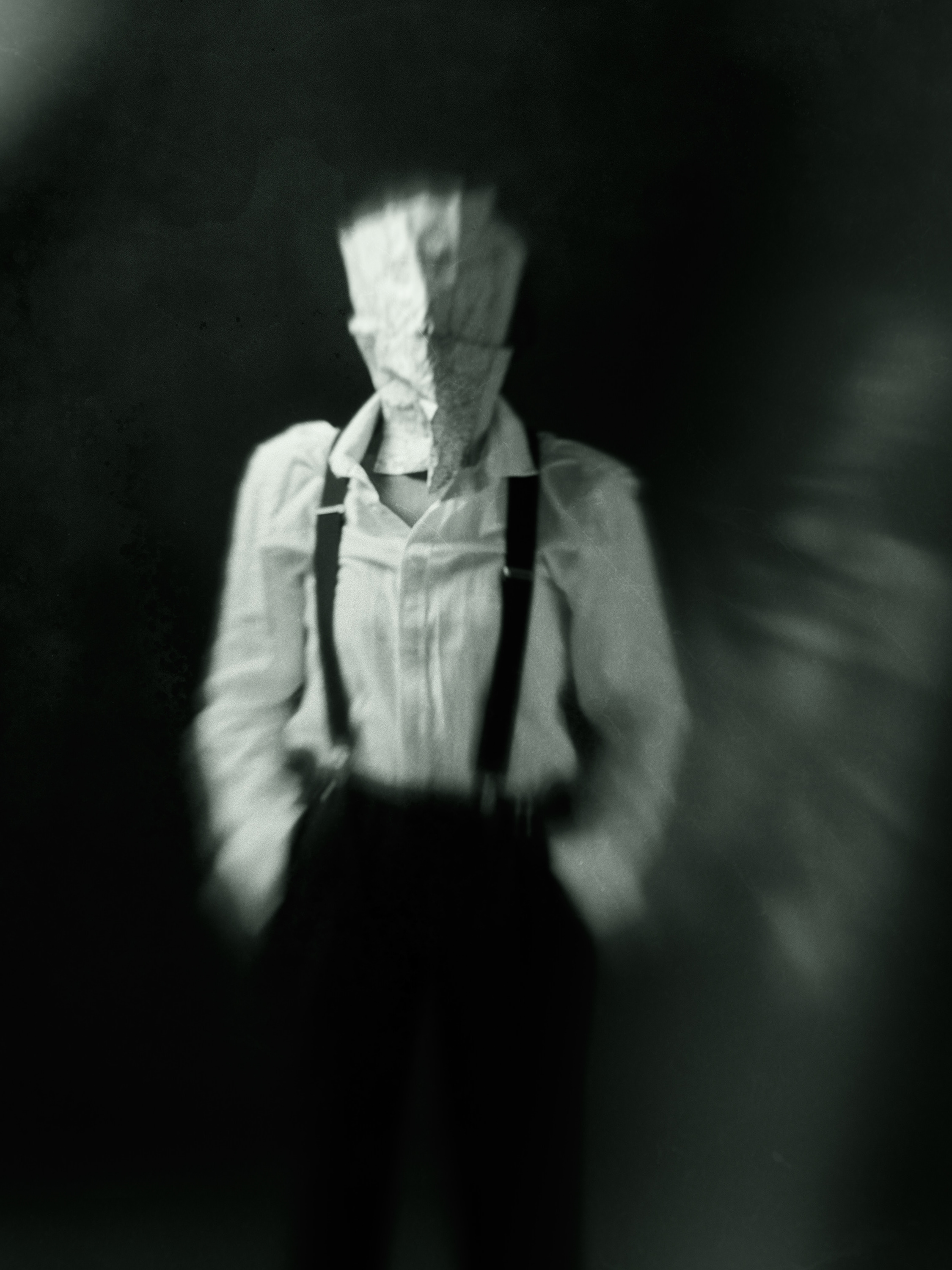

Over time, I’ve taught my camera to follow that way of seeing. Motion blur, overlapping sequences, soft edges — they all help me convey the rhythm of remembering. Every encounter has its own pulse, its own movement, changing and reframing itself as it settles into memory.

On another level, I want my photographs to express what it feels like to meet someone. When I look at a face, my eyes don’t linger on every detail, every imperfection. Instead, they move through a sense of presence — that moment of connection that exists between two people. That’s what I try to capture. I’ve always admired how Witkacy approached portraiture, not as a means of likeness but as a reflection of energy, mood, and encounter. My portraits don’t claim to resemble the sitter precisely; they speak about the meeting — a point in time filtered through my own emotions. I’m not a photobooth artist, after all.

There’s also a quiet insistence on imperfection in my work. I never retouch my portraits or polish away their rawness. I’m drawn to the Japanese idea of wabi-sabi — the beauty found in imperfection and transience. For me, those so-called flaws are marks of life — traces of a real person rather than an idealised artefact.

Technically, I experiment with creative processes such as multiple and long exposures, on-camera filters, and my beloved Lensbaby Velvet 50mm. Each tool helps me translate the intangible — the emotional undercurrent — into something visual and honest.